What Is Meant By Serial Monogamy In Sociology

Monogamy is a form of relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime or at any one time (serial monogamy), as compared to polygamy, polyandry, or polyamory. The term is also applied to the social behavior of some animals, referring to the state of having only one mate at any one time.

Contents • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Overview [ ] The term monogamy is used to describe for different relationships. A Love Supreme John Coltrane Pdf Writer. Biologists,, and often use the term monogamy in the sense of sexual, if not genetic, monogamy. Modern biological researchers, using the, approach human monogamy as the same in human and non-human animal species.

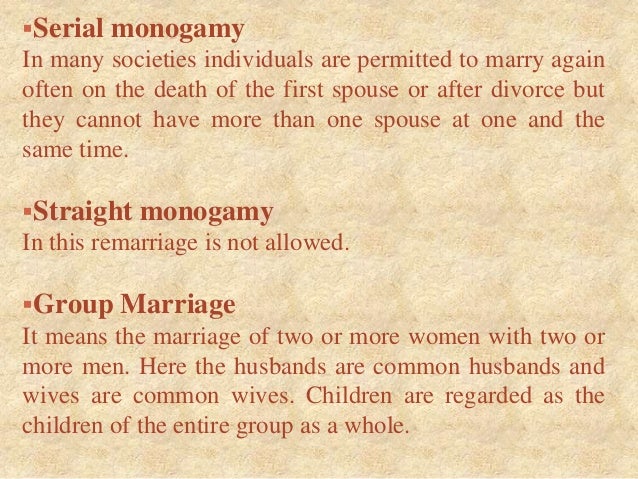

They postulate the following four aspects of monogamy: • Marital monogamy refers to of only two people. • Social monogamy refers to two partners living together, having sex with each other, and cooperating in acquiring basic resources such as shelter, food and money. • Sexual monogamy refers to two partners remaining sexually exclusive with each other and having no outside sex partners. • Genetic monogamy refers to sexually monogamous relationships with genetic evidence of paternity. When cultural or social anthropologists and other use the term monogamy, the meaning is social or marital monogamy. Marital monogamy may be further distinguished between: • marriage once in a lifetime; • marriage with only one person at a time ( serial monogamy), in contrast to or; Human monogamy's legal aspects are taught. There are also aspects in the field of interest of e.g.

And, as well as ones. Etymology [ ] The word monogamy comes from the μονός, monos which means alone, and γάμος, gamos which means marriage.

Frequency in humans [ ]. A pair of parrots. Biological arguments [ ] Monogamy, or at least social monogamy, does exist in many societies around the world, and it is important to understand how these marriage systems might have evolved. In any species, there are three main aspects that combine to promote a monogamous mating system: paternal care, resource access, and mate-choice; however, in humans, the main theoretical sources of monogamy are paternal care and extreme ecological stresses. Paternal care should be particularly important in humans due to the extra nutritional requirement of having larger brains and the lengthier developmental period. Therefore, the evolution of monogamy could be a reflection of this increased need for bi-parental care. Similarly, monogamy should evolve in areas of ecological stress because male reproductive success should be higher if their resources are focused on ensuring offspring survival rather than searching for other mates.

However, the evidence does not support these claims. Due to the extreme sociality and increased intelligence of humans, H. Sapiens have solved many problems that generally lead to monogamy, such as those mentioned above. For example, monogamy is certainly correlated with paternal care, as shown by Marlowe, but not caused by it because humans diminish the need for bi-parental care through the aid of siblings and other family members in rearing the offspring.

Furthermore, human intelligence and material culture allows for better adaptation to different and rougher ecological areas, thus reducing the causation and even correlation of monogamous marriage and extreme climates. However, some scientists argue that monogamy evolved by reducing within-group conflict, thus giving certain groups a competitive advantage against less monogamous groups. Paleoanthropology and genetic studies offer two perspectives on when monogamy evolved in the human species: paleoanthropologists offer tentative evidence that monogamy may have evolved very early in human history whereas genetic studies show that monogamy evolved much more recently, less than 10,000 to 20,000 years ago. Males are not monogamous and compete for access to females. Paleoanthropological estimates of the time frame for the evolution of monogamy are primarily based on the level of seen in the fossil record because, in general, the reduced male-male competition seen in monogamous mating results in reduced sexual dimorphism.

According to Reno et al., the sexual dimorphism of Australopithecus afarensis, a human ancestor from approximately 3.9–3.0 million years ago, was within the modern human range, based on dental and postcranial morphology. Although careful not to say that this indicates monogamous mating in early, the authors do say that reduced levels of sexual dimorphism in A. Afarensis 'do not imply that monogamy is any less probable than polygyny'. However, Gordon, Green and Richmond claim that in examining postcranial remains, A. Afarensis is more sexually dimorphic than modern humans and chimps with levels closer to those of orangutans and gorillas.